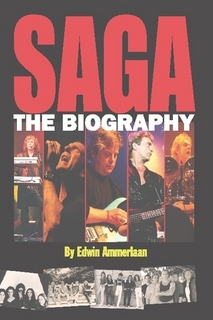

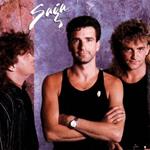

NEGUS: from Saga to the Collective ~ an interview with Steve Negus and George Roche

by Live Music Head

Hailing from the city of Oakville, Pockets was the original name for the

progressive rock band Saga, before they changed it in 1977

With a rhythm section from Fludd

Ian Crichton on guitar and Michael Sadler on lead vocal

Saga began tearing up the charts in the early 80s

with hit songs such as Wind Him Up, On the Loose,

Don’t Be Late, and Scratching the Surface

And with equally successful videos to accompany them

Saga was awarded the 1982 Juno for

Most Promising Group of the Year

Steve Negus, a Grimsby native

now living in east Hamilton, Ontario

not only co-wrote these songs with Saga

but he was their original drummer until

announcing his departure in 2003

Mr Negus, along with his manager George Roche,

joins me now to discuss the history and

what’s been going on since his retirement

Growing up with Hamilton radio station CKOC, what music were you hearing that led you to form your own band at the age of 12?

I use to collect the CKOC charts, but I got interested way before that. I was born in 1952 so I would say somewhere around ’60-’62, I started getting into surf music. My first album was The Beach Boys. I was also listening to Jan and Dean, The Safaris and the Ventures. You weren’t considered a drummer unless you could play Wipe-Out.

After high school, you came to Toronto to work at a bank. Can you tell us what led up to quitting your day job and joining a band called Bananas?

I was working for the Bank of Montreal at Bay and Wellesley and two weeks before I was due to write my accountant exams, I looked around the bank and thought, I don’t want to do this. I really don’t want to do this.

You mean, you didn’t fit in with the Bay Street crowd (laughs)?

I was playing in a country band six nights a week plus a Saturday matinee at the Winchester Hotel in Cabbagetown. There were four of us guys living in this mouse-infested apartment just around the corner from the bar. These days the area is high rent, but back then it was pretty seedy. One guy worked at a pizza store, one guy was going to George Brown College, and there was a guitar player. I use to get up in the morning and put a suit on. At night I’d take it off and go play country music.

And on ten minutes sleep probably?

That’s it. I could do that then! (laughs).

But now it’s hard isn’t it? Even without the booze. (laughs)

Absolutely. The guy who worked at Bobby Orr’s Pizza would come home around 4 in the morning with a pizza every night. We’d stay up and eat it. But after quitting the bank, I went to Long and McQuade and pulled three numbers off the bulletin board. One of the three was for a band called Bananas. After doing the usual audition thing, I got the gig as their drummer. After a few rehearsals we started performing. Bananas later became one of the top show bands in Toronto. We played the El Mocambo, The Jarvis House, and a place called The Generator at Yonge and Eglinton. These were great gigs and we made great money back then.

What about the Le Coq d'or Tavern on Yonge St? Did you play there?

Bananas didn’t, but I use to hang out there. It was the only R&B club on the strip. They’d bring in these American black bands like Tavares and the President's Band. I’d go down and sit in with some of them. They use to call me “blue eyed soul brother” (laughs). I’d say, “what are ya talking about? I don’t have blue eyes” (laughs). At that point in my career, I still wasn’t all that serious about playing but I liked the whole thing about you know, meeting women. But while I was in Bananas, I heard a band called Tower of Power.

Oh, I love them! I saw them at BB King’s bar in New York last November.

Tower of Power changed my life. As soon as I heard this band I thought, I gotta play that! (David) Garibaldi, the drummer, is one of my greatest influences. A lot of my style comes from the R&B side of things, so that’s why I liked sitting in at the Coq d’or. I loved playing the funk stuff. It’s drummer’s music. So I quit Bananas and started my own R&B band. We did a whole summer in Wasaga Beach at a place called the Dardanella.

Was this the band called Shelter?

Yes, and it started out as a six-piece R&B band; two black singers, Betty and Otis; a black guitar player; and three white guys, one on bass, one on keyboards and myself on drums. We played stuff like Gladys Knight and the Pips and Tower of Power. But while we’re playing the Dardanella gig, Betty got herself pregnant and left to have an abortion. My six-piece R&B band went down to five. Otis Gale, who we used to call Leroy (laughs) gets haemorrhoids, but he tells the doctor he’s constipated instead, and the doctor gives him a laxative! The next thing you know Leroy’s in the hospital having his haemorrhoids removed and my six-piece R&B band goes down to four. The only other guy who sings is the guitar player. One night during the middle of the second set, the guitar player starts falling back and leaning on his amp. “I can’t play,” he says. “What’s the matter?” I ask him. “I did angel dust.” We take him outside and walk him around, but he’s saying stuff like “why do I exist?” (laughs). My six-piece R&B band is now three white guys who don’t sing! Across the street there was another R&B band playing at The Windjammer and we had good camaraderie with their singer, Mighty Pope. When Mighty Pope heard what was going on, he’d come sit in with our band and then run back and do his own. Needless to say at the end of the summer, Shelter went their separate ways.

After packing in Shelter, you went on to join Fullerton Dam and then eventually became the drummer for Fludd which led to The Pockets, who became Saga.

Fullerton Dam was an original rock band with Grant Fullerton. In order to play Grant’s original material, I suddenly had to take my R&B chops and start playing with baseball bats on a big double kick bass drum. Grant had been with bands like Stitch in Tyme and Lighthouse and still performs today. But back then, the band was struggling. We did one album together on Condor Records, but it was a tough go playing original material. One night while playing at Larry’s Hideaway (long gone now), the boys from Fludd came in, scouting for a new drummer to replace Ian McCorkle. McCorkle also played in the progressive rock band Breathless with Jeff Plewman, aka Nash the Slash. McCorkle really suited the role with his long blonde hair but Fludd fired him because his timing was suspect. When Brian Pilling said, “we’re shopping for a new drummer and he’s sitting right here.” I had to go through the decision, “well, should I stay with Grant because I’d been with him for two years?” or “should I take this gig with Fludd?”

Fludd were already an established band at this point?

It was around 1975 and Fludd already had success with Cousin Mary. I decided to take the gig. But what happened was, Brian had leukemia. He had it when I joined the band but it was in remission. Everything was fine until his remission broke down and the band came to an abrupt halt. At that point Fludd was Peter Rochon, Jimmy Crichton and myself, and the Pilling brothers. But when this happened to Brian, we realized we couldn’t continue the band as Fludd. Together with Jimmy Crichton and his younger brother Ian on guitar, Peter Rochon and Mike, who had sang with Jimmy in a band called Truck, we formed Pockets. We rented a rehearsal space at the old Phillips building at Leslie and Eglinton and set up shop to work eight to ten hours a day, six days a week. We ate peanut butter sandwiches to survive. We did two months out of town, our first being at Tudor Tavern in Cambridge to a room of six people and we did some stuff in Quebec too. But the first thing we did in Toronto was simulcast on Q107 from Thunder Sound, which I think is gone now too. It was a Sunday night and we played straight to air, and then the next night The Pockets opened at the Piccadilly Tube, which is also gone. It seems they’re all gone now. But we did two weeks at the Piccadilly and packed it every night.

So how did you go from six people to packed rooms every night?

Well Cambridge is a small town. We were a band they’d never heard of, so why would they go see it? Fludd were really well known in Toronto and people made the connection to The Pockets. At that time, we were in Phase One studio too, working with Paul Gross who basically fronted us studio time so we could start the first Pockets album.

Who is Paul Gross?

Paul produced the first three Saga albums with his partner Doug. Doug also worked with Triumph. There was a ton of stuff going on at the time. I think some of the original Honeymoon Suite was done there, and I believe Bryan Adams recorded there as well. It was THE rock studio.

So between the rehearsal space, Phase One studio, and the Piccadilly Tube, Pockets became Saga?

Once we finished the first album we discovered there was already a band called Pockets so we couldn’t use that name. It was our manager who came up with the name Saga because of the continuing story aspects of what we were doing lyrically at the time.

Looking back through all this history, when did you first acquire the title Lord of the Drums?

That was actually toward the later days of Saga when I started getting older (laughs). By being in Saga I had gained notoriety for my style of playing. My signature was also recognizable when I played on Don’t Pay the Ferryman by Chris DeBurgh. Lord of the Drums was a name my webmaster came up with and it stuck, but there’s no real story to go with it.

You mentioned Garibaldi, but who are some of the other drummers and percussionists that have influenced you?

Garibaldi is probably my biggest influence and I think every rock drummer is influenced by John Bonham. I met Led Zeppelin on the tour before Bonham died. We were performing with Styx in Germany during the Grand Illusion tour (1980) and Led Zeppelin was playing on the same night, so we ended up in a bar with John Paul Jones and Robert Plant. In Germany, if you’re a resident at a hotel, the bar stays open until you leave. I stayed in the bar with those guys till 8 in the morning drinking schnapps and beer! I’ve never been a big jazz guy, but another drummer who’s influenced me is Dave Brubeck’s drummer, Joe Morello. In 1961, my music teacher gave me a copy of Time Further Out and if you look on Youtube, you’ll find early footage of Take Five and Morello playing around with time signatures, back before no one else ever thought about it.

During your time with Saga, there were sideline projects in the works. Was it necessary to leave Saga in order to focus on other creative pursuits?

Something I told Jimmy Gilmour when he first joined Saga was, “you’re destined to spend your whole life being somewhat frustrated. If you’re not frustrated, the creative juices can’t flow. In other words, if you’ve done everything you can as a musician, then you’re ready to retire.” Even though Saga was at the pinnacle of success and Worlds Apart the most successful recording, Jimmy Gilmour and I were frustrated. When Head or Tales was released and didn’t do as well, we all looked at each other wondering why. There was dissention in the ranks, if you like, where Jimmy and I felt some of the issues should have been handled differently. We were pushed out of the band and I think it had a lot to do with management. If they cut the pie three ways instead of five, Saga could make more money.

But Saga didn’t go on as a three-piece, did they?

No, they hired side men to replace us. They left us with no equipment for over a year and we had to get lawyers to settle. Jimmy and I decided to do our own album. We hooked up with Robbie Rae, who had a hit with Que Sera Sera.

Que Sera Sera, the Doris Day song?

The dance version.

The Canadian dance version of Que Sera Sera? (laughing). You learn something new every day!

Robbie thought I was gay. When Jimmy and I asked him to sing on our stuff, he thought I was trying to pick him up (laughing). But he did join us and we released an album as GNP. Shortly after that, Jimmy decided to go to Frankfurt to attend the Namm show (trade shows where new music equipment is presented) and while over there, Jimmy met up with Mike Sadler (the singer from Saga). Their conversation set the basis for Jimmy and I to reunite with Saga.

But wasn’t the material for GNP already formulating before you were pushed out of Saga?

No. After the first three Saga records, the band moved to England. We lived together to write the fourth album while our agents went looking for producers. Rupert Hines came up and we decided to do the next album with him. Rupert is a brilliant producer. We did the album at Farmyard Studios in Little Chalfont. Rupert and I developed a great relationship and because he liked the sound of my drums in the old farm, he called me in when he produced The Getaway record for Chris DeBurgh. When I started work on that, DeBurgh handed me a cassette with a synopsis for each song, which I thought was absolutely brilliant. Chris is a singer songwriter who actually lets you play what you want and to get that kind of freedom is unbelievable. It was part of what caused the light bulb to go off in my head. Saga always wrote the music first and then jammed the lyrics and melody after the fact. So what we ended up with was a great piece of music, but not necessarily a great song. I thought DeBurgh’s way was a better way to write songs but, when I tried to take this back to Saga, they didn’t want any part of it. This added to my unrest, if you will, that led to my departure.

Were you involved with most of the song writing for Saga?

Saga wrote music mainly as a collective when it came to the actual music side of it. Michael Sadler and Jimmy would do most of the lyrics and melodies. I wrote lyrics in the early days, but they never got recorded.

I saw a Youtube clip of a song called Pick Up the Phone. This is an original song you wrote as a three-piece under the name Negusis. Can you tell me more about this band?

While with Saga, I had presented an album’s worth of material but they either didn’t like it or they didn’t listen to it, I’m not sure which. So I ended up sending some of my stuff to Al Langlade. Langlade is a singer who wanted me to produce him, but I always said no. I didn’t like his songs. But when I got my stuff back from Langlade with his vocal on it, I almost fell over. It was Dare to Dream! I heard the lyrics and melody with his voice and thought, wow! The seed had been planted. Langlade lives in Thunder Bay and I live in Hamilton, so when I was pushed out of Saga, I joined an 8-piece R&B band called Power House, while Langlade and I worked over the internet. And it was with the bass player and guitar player from Power House that led me to form Negusis.

Are there any similarities between writing with Langlade and writing with Saga?

Yes. Back in the early days of Saga, there was a lot of me in the songs, especially from the groove stand point. The thing that made Saga different from other progressive bands was my R&B background. The grooves are totally different from say, what King Crimson, Yes, Genesis or Rush were playing. I was actually compared to Neil Peart back then, but apart from the fact we both play drums and grew up five miles from each other, there is no other comparison. Neil plays from a prog rock angle with a lot more time signatures. But back in the day, the big three were Rush, Max Webster and Saga, so we did shows at Maple Leaf Gardens and Saga and Rush toured together. All coming up at the same time, of course there were comparisons. This was our peer group. The groove of me is inherent in the early Saga stuff but it wasn’t renewed until I began writing with Langlade. Now I’m having fun again with a great band.

Do you enjoy working in the studio?

I love studio work. I’m as comfortable in the studio as I am on stage. They do different things for me, but I like them both equally. Being in the studio can be tedious, but it’s where you take your ideas and develop them. You have to put in the time to get the essence of the song out. It doesn’t just come with playing the chords, at least not for me. With my music, it’s like writing for orchestras with elements and counter melodies and all this subtle stuff going on. You’ll hear new stuff in the arrangements even after listening to it a hundred times.

Langlade is also the vocalist in the Negus band, along with Kelly Kereliuk on guitar, Ian Nielsen on bass and Matt Whale on keyboards. Will fans be hearing strictly Negus originals at your shows, or do you also perform material from Saga?

What I’m doing at my shows is a compilation of all the history we’ve talked about. I’m doing a Fludd song, a Chris DeBurgh song, and although we did In Your Eyes at one show, we haven’t been doing any GNP. I’m hoping to have Ed Pilling come out and do What an Animal, one of Fludd’s big hits. And of course we’re doing Saga stuff. We take Saga tracks, and give them slightly different twists to see how it feels in the show. We change it up to find a nice mix.

When I was re-visiting Saga songs prior to this interview, I thought my god, I know all these songs. I know all the words! (laughter) And I was reminded just how many hit songs you had. And not only the songs, but Saga had many videos playing on television.

Saga came out right at the time when MTV was breaking. MTV showed our videos to death because there weren’t that many to show at the time. Saga was touring the States extensively with Pat Benatar, Billy Squire, Heart, and Jethro Tull. By playing our videos regularly, MTV really helped break us in America.

For years now, Canadian artists have to go to the United States to make a name for themselves. I think it’s still that way. Saga not only toured the States, but became huge in places like Puerto Rico. What are your thoughts not only on the Canadian music industry today but the music business in general?

Most Canadian artists have to go someplace else to be successful. I think its part of the Canadian psyche. We have this thing in our head, an inferiority complex.

We need somebody else, other than a Canadian, to tell us we’re good?

Exactly.

I grew up thinking that.

Of course you did. Until somebody else accepts it, it’s just Canadian so it can’t be good. Now, this is the problem that all Canadian artists, including myself, are still having. There is very little support from Canadian communities and with the collapse of the music industry, we’re now faced with situations whereby most bands can’t afford to play. This brings us to The Collective, which George (Roche) and I want to talk about.

George Roche, manager of Steve Negus and Executive Producer of Lucid Productions joins the conversation.

GR

In order to get the notoriety and recognition originally brought about by the record companies, musicians now have to rely on their own pragmatic skill. With record companies looking after it, bands didn’t need to hone their own business skill or be required to manage the manager. Bands only had to get to sound check on time. Due to the advent of the internet and the inauguration of Youtube, the record industry has imploded. The artist now has to wear all the hats. Artists have to rely on their own resources to bring their music to the field. And the internet and Youtube are mediums that even the record companies now say bands have no choice but to use. But how do we compensate the artist fairly? This is the biggest glitch. It’s amazing that the current mindset has no guilt and no shame whatsoever of going on line and accessing Steve’s or anyone’s music for free. It wasn’t long ago you’d be sued for this.

SN

Performing live is the only real source of revenue left for musicians. And I think in order to make it a healthy environment again, we have to go back to a grass roots level and build an audience from there.

Online social networking sites like Facebook and Myspace are very powerful and many of us like using them to promote music. It’s the first and foremost reason I use them. But the market is saturated and I’m not altogether sure if these sites are being used effectively.

GR

The internet is helping to build our team in ways that were never possible before. Years ago you couldn’t find people as easily as we can find them now. You had to know someone who knew someone who knew someone. Now you can find people on Facebook with the click of a mouse. Technology has worked against the industry but there are also many ways to benefit by it. However, let’s take it one step further. The results people will experience will only come from what’s been properly stated. Word of mouth is only as effective as the communication style being used to elicit a response. If the communication style is ineffective, word of mouth in itself is just another ineffective tool. The formulation of the communication strategy is the beginning. Lisa, remember when we were on the phone? Afterward you sent me an email to say “what a great conversation we were having, too bad my phone died”. Think about that for a minute. It’s the inspiration from that kind of conversation that keeps us here. Get that interesting conversation going and the market will listen. But if it’s the same old hat and repetition of the old ways, you’re done. It’s got to be a new pitch, a new way of thinking, a new conversation. And when people feel that newness, it will motivate them to action. It’s all about the emotional. Yea! Yea! Yea! It’s about taking the necessary steps that are congruent to the current climate requirements. I still got musicians saying, “I’m a fucking rock star, where’s my guarantee?” And I’ll argue with them on the phone saying, “if you’re looking for a guarantee, you’re stuck in the 80s.” It’s lead, follow or get out of the way.

The Grateful Dead who based their entire 40-year career on the live experience and building their fan base from a grass roots level, have the most loyal and dedicated fans on the planet. And it’s still going strong. But at the same time, the late Jerry Garcia was quoted as saying, “the music should be free”.

GR

The Grateful Dead were future-proofed years ago. Bands back then were applauded for releasing independently. Challenge the machine! Say no to the record companies! This showed character and heart. You were courageous to be able to do this and you were applauded. But these are not the times for sticking your tongue out at the people who were once feeding the industry. If you can’t afford to produce your own material now, you’re not going to get it released independently or otherwise. If you take an independent working band who gigs twice a month, in the end that band will have incurred over $100 per gig related to gas, cell phone bills, media, graphic work and equipment rental expenses. Most are out of pocket before they hit the stage and probably will lose money. Not to mention those bands that have members who hold down jobs, who don’t have the time to invest in performing the tasks necessary to effectively market and advertise their act. In any case, that’s $1200 per year to a band playing six months of that year, and it’s pale in comparison to what it would cost to market a band using more aggressive strategies. No matter who you are, the question is "where are your followers and how many are showing up?"

SN

When I tried to get the Negus band out to play, I couldn’t find an agent. All the agents are booking these days are tribute bands. It’s the tribute bands that are making money. But by only booking tribute bands, the club owners and agents are destroying original music. Agents laughed at me when I said I wanted to book my original band. “ha, ha... sorry, I just booked an Abba tribute this week”. I don’t want to play in a tribute band.

GR

Its robbery compared to say, Germany, where the music scene has always been very proactive. Germans have their own music outside of the international stuff. Every fourth song on the radio has to be German and be sung in German.

But Canada does have their own music and our radio stations are regulated for Canadian content.

SN

But where do they get it from? Years ago it was Gordon Lightfoot and Anne Murray and I guess now Saga fits into that as well. You’ll hear Wind Him Up and On the Loose but they don’t get their Canadian content from new artists, only from Canadian gold. This has been going on for years. It’s the old Canadian way of just playing it safe.

Okay, so who exactly is The Collective and how will they make the difference?

GR

The Collective are willing to address the issues most want to ignore. Nothing will change unless it’s acknowledged. Many have accepted the mediocrity as if there’s no other solution. What it comes down to is the strength of any one initiative and the amount of people who buy into it. One or two people can’t change the world. The strength of the numbers will be realized by people who get the thinking. We can only conquer the conquerable by working with the workable. Whoever is interested in seeing a change, will want to take risks and get outside the box, and not live in this mediocre comfort zone. By staying in the box, we stagnate and stunt our growth.

SN

To answer your question more specifically, The Collective is artists, photographers, video people, journalists, you, marketing, management, agents, promoters, and everyone else on the credits. What we have to realize is, without each other we have nothing. We have to pull together, pool our resources and donate our services, so that we have some power to get out there and perform.

When you say donate services, do you mean donate money?

SN

No, it’s not about donating money. Bands are going to clubs and asking “can I get a gig here?”, and the club owners are telling them “give me 1200 bucks, bring the audience and market it, and you can have a gig here”. This is not easy to do, but if everyone involved in the field combines their efforts, The Collective can promote, take care of sound, the lights, the door, and whatever else needs to be done. We can do this ourselves! We’ll pack the place and the club can have the bar. Most of The Collective will work for, if not nothing, next to nothing, at least as we develop and build our team. Eventually the money will come to get paid for our services.

GR

Club owners would have no reason to say no because we’ve solved their problems. And we’re not looking for the guarantee. We believe with the skills, experience, knowledge and efforts of dedicated people, we won’t need the guarantee. It doesn’t make sense to leave everyone in a segregated position when we’re all vying for the same attention, the same market, and utilising the same resources. Everyone may as well be brought on line to better the pragmatic game board. One of the biggest problems out there right now is the disconnection with relationships. It all has to get harmonized. The Collective is the answer but it has to be credible. It will really come down to credibility. I personally cannot stand seeing a stage wasted on Mustang Sally. It drives me up the wall. I don’t want to knock the guys who are out there playing Mustang Sally and Brown Eyed Girl, but I want The Collective to be about the dedication and commitment found in creativity.

But really, how will this be any different? How will you prevent the egos that led to the greed that caused the collapse of the music business to begin with?

GR

We’ll be running it, and we’ll have the decision making powers to say....

But that sounds like another record company to me.

GR

But with record companies you didn’t have a choice. The negativistic way which took over the industry is a learned way of thinking. This psychology needs to be addressed. It comes from being conditioned by negative messages sent by those running the businesses. We need people desirous of change. But there’s no point in pitching a monkey on this if he doesn’t understand the language. We’re going to start with the people who already get it, and bring them on line. They will become the foot soldiers and the teachers. I think that’s what it will take. We need the role models to restore the integrity on this thing. With The Collective, bands come and we audition them. We’ll have competent people looking at the skills of the band. If they’re not up to the standards of the Collective, we’ll send them to the amateur division at The League of Rock, for example (see LOR website link at the end of the article). Terry Moshenberg at the League of Rock provides an environment where bands can find out if being a professional musician is something they’re really up for and really want to do.

Little Steven (Van Zant) says a band only gets good by playing covers. A band has to play in a bar six nights a week, paying their dues, before they’ll ever be any good.

GR

But you know what happens? When you’re done with those bars, the majority of bands don’t make it back. The majority! Clubs are scrutinizing and they’re very prejudicial. It doesn’t matter how good you are, the club only cares about the bottom line. Bands then have to go find new venues to play in. We want to keep everyone at the same level. But there has to be some integrity. There has to be dedication and commitment on the band’s part. The ID cards The Collective hands out will be indication enough. When clubs see our card, it will say, “oh this guy has been approved by a body of people who want to put out good music”.

SN

There are also phenomenal photographers who we’ve made part of our team. These photographers would be made available to not just my band, but for all who join The Collective. It will enable us to better do what we do, just as it does for you as a journalist. As a journalist for example, by joining the Collective, we could feed you new artists as it grows, and you could write about it. It’s a win-win situation.

Looking at stadium shows these days, I don’t know how much longer music fans will continue dishing out money for the ticket prices they’re charging. It’s been on the decline for a while I think, yet if Live Nation and Ticketmaster merge, live music may only be experienced by the elite class.

GR

I won’t buy from Ticketmaster. But isn’t it interesting? Ticketmaster are seeking their next of kin to work with, just as musicians are. I talk with all kinds of managers and we benefit largely from our exchange of information and our own findings, which in many ways can be serendipitous, ya know?

Bob Lefsetz, the industry guy who goes on and on about the need for this kind of change has very strong opinions which caused a heated debate with Gene Simmons at the Royal York Hotel during the last Canadian Music Week in Toronto. Lefsetz argued that Simmons’ new record label will take off initially because of the Simmons name, but ultimately it will fail because he uses the old model. I guess you both agree with Lefsetz?

GR

Anything Gene Simmons touches turns to money. He’s Gene. But once we figure out what the communicative words are going to be, The Collective spiel will be what moves people. It cannot be the same message. If you’re going to survive in the Canadian music industry, you have to be proactive, pro-social, and do it deliberately. What’s going to happen? Are the clubs going to become extinct? Are we going to shut down the entire industry because there won’t be any places left to play? Will there be a rebellion? If we don’t get control of this thing now, that could very well happen. Interestingly, entertainment revenue is the second thing central to the local economy. Most people don’t realize it. If you get a divorce, entertainment expenses are on the table as a legitimate expense. But what I’ve learned is Canada is very apathetic. I think we’ve been trained to be. People treat you the way you teach them how to. The negativistic business practices that have run the industry has led us to apathy and stagnation. There’s so much distrust and so many people getting screwed. How can anyone think about what they can do for the Canadian music industry when all that’s on their mind is the next guy who’s gonna fuck them? This is not the state of mind to be pro-active, pro-social, a planner, a contributor, or a teammate! The power has been placed in the wrong laps for many years. Power should be shifted to the people actually doing the work, the hands-on people.

Is the Collective open to all genres of music?

GR

It’s about matching the right resource with the right opportunity. I just did sound for Walter Asternack on the weekend. I added him to the list because I realize there could be blue hairs down the road who want to hear polka!

Is the Collective an established entity right now? Will it require registration?

GR

You’re talking TMA. The Toronto Musician Association was a sham. They offered legal advice and they offered a lot of things to the artists who paid membership money, but TMA delivered nothing. Any situation I ever heard of where the TMA was involved, claims were never delivered upon. I think it fizzled out when artists stopped paying their dues. Tragically, our own government doesn't seem to know how to build legislation to defend our artists and their material, but they have that protection and legislation firmly in place for the film industry, don't they? One of the focuses of The Collective will be to address those issues with a united front on matters. It's time to really begin utilizing our resources to promote a quality of life within the music industry that doesn’t exist right now. In my view, for that to be achieved, everyone must agree that we are all in the same boat and, if that boat tips over, we ALL get wet. A partnership is not about one person having a better chance at profit than anyone else involved. That's greed. The Collective is about fairness and equality. The ME ME ME! has got to go. It's back to grass roots. "You work for me" has been edited to "we are working together.”

SN

I think if we all work together, we’ll all win. We won’t be dealing with a cultural wasteland.

Quelle: http://livemusichead.blogspot.de/2009/11/negus-from-saga-to-collective-interview.html